Seeing neonates in the Emergency Department makes me nervous. Hopefully this review can simplify one of the more common neonatal presentations. Following are the key points emergency clinicians need to know about neonatal jaundice.

- Neonatal jaundice is often physiologic, not pathologic

Almost all newborns will develop a bilirubin level above the normal cutoff for adults (1 mg/dL) within the first week of life. This is due to increased bilirubin production and decreased hepatic bilirubin clearance. Typically, levels will gradually increase, peak around 6-8 mg/dL on the third day of life, and then decline to normal within 2 weeks. Jaundice often occurs at bilirubin levels >5 mg/dL, and many infants will have visible jaundice at some point. This normal process is termed physiologic jaundice of the newborn.

- The second most common cause of neonatal jaundice is breast milk jaundice

Breast milk jaundice refers to a prolonged hyperbilirubinemia beyond the first week or two of life. It can be thought of as a persistent physiologic jaundice. The mechanism of breast milk jaundice is unclear. Neonates will often have bilirubin levels above 5 mg/dL for several weeks that typically returns to normal by 12 weeks. Neonates should continue to have their bilirubin levels monitored during this time, however they should continue to breast feed as normal. If levels rise significantly above normal or if they develop a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, they should be evaluated for pathologic causes of jaundice.

- There are numerous pathologic causes of neonatal jaundice

Pathologic causes of neonatal jaundice should be suspected for:

- Jaundice within the first 24 hours of life

- Any elevated direct bilirubin level

- Rapidly rising or persistently elevated bilirubin levels

- Bilirubin levels approaching exchange transfusion cutoffs (see below)

Jaundice within the first 24 hours of life suggests ABO incompatibility between mother and neonate resulting in significant hemolysis. Typically this will occur with a mom with O type blood and a child with either A or B.

Elevated direct (conjugated) bilirubin suggests an obstructive process such as biliary atresia.

Other causes of pathologic hyperbilirubinemia include INFECTION/SEPSIS, breast feeding failure and dehydration, inherited red blood cell disorders, genetic defects in bilirubin metabolism, and reabsorption of cephalohematoma. In the Emergency Department, finding the exact cause of hyperbilirubinemia may not be as important as identifying it in the first place and initiating treatment. Unless, of course, the cause is sepsis.

- Evaluation and treatment of hyperbilirubinemia is relatively straightforward

Every neonatal jaundice patient presenting to the Emergency Department should have bilirubin levels checked, both direct and indirect. If the patient is well-appearing, this may be all that is necessary. Further testing is dictated by patient’s circumstances. A jaundiced neonate <1 day old should have a CBC and Coombs testing. Direct Coombs will look for presence of maternal antibodies on the baby’s red blood cells. Ill-appearing patients should have a full sepsis workup. Patients with elevated direct bilirubin may require surgical consultation, given the possibility of biliary tract obstruction (i.e. biliary atresia) and cholestasis.

The treatment of hyperbilirubinemia is primarily focused on preventing bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND) and its related, long-term neurologic complication, known as kernicterus. Bilirubin levels greater than 20-25 mg/dL place patients at increased risk of BIND. The two treatments available are phototherapy and exchange transfusion.

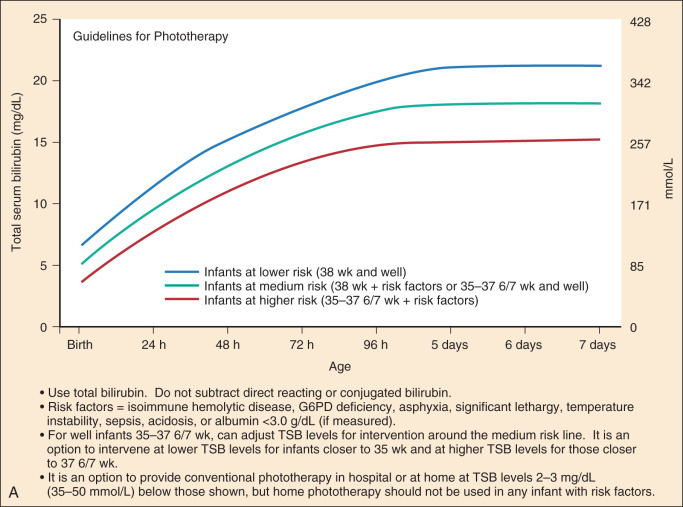

The American Academy of Pediatrics have two simple graphs that function as guidelines for when to use phototherapy and exchange transfusion. Patients are first divided into a risk category (low, medium, high) based on several clinical factors including prematurity. Their total bilirubin level is then plotted on the graph for their specific age. Those above the specified threshold should be treated appropriately. A simple online version of this is available at BiliTool.org.

It should be noted that these graphs are not based on robust evidence, therefore treatment with exchange transfusion can be initiated based on clinical judgment. For example, jaundiced neonates with symptoms of BIND should proceed with exchange transfusion.

In summary:

- Neonatal jaundice is often physiologic

- Direct hyperbilirubinemia is always pathologic – think biliary atresia

- Hyperbilirubinemia in the first 24 hours of life is always pathologic – think ABO incompatibility

- Ill-appearing patients require more extensive testing – think sepsis

- In well-appearing patients with jaundice, use the bilirubin graph to guide treatment with phototherapy and exchange transfusions

References:

Maloney, Patrick. Gastrointestinal Disorders. In: Walls R, Hockberger R, Gausche-Hill M. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, Ninth Edition Philadelphia, PA: Elsivier Inc; 2018.

Wong, Ronald, Vinod Bhutani. 2017. Pathogenesis and etiology of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn. UpToDate. Accessed January 2, 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-and-etiology-of-unconjugated-hyperbilirubinemia-in-the-newborn?search=neonatal%20jaundice&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~97&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia: Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 114:297–316, 2004.

Charles Murchison

Latest posts by Charles Murchison (see all)

- Benign Early Repolarization vs. Anterior STEMI - February 20, 2020

- Can experienced clinician gestalt + ECG accurately exclude acute MI? - August 20, 2019

- Does Observation for ACS Make Sense? Part 3: Risk Stratifying for Adverse Cardiac Events - June 20, 2019

0 Comments