While we may be trapped in our concrete jungle here in Brooklyn, many of us and some of our patients do occasionally get outside. In the Northeast in particular, this means a high risk of getting a tick bite and contracting everyone’s favorite zoonotic disease: Lyme Disease.

This past month’s Wilderness Med meeting we talked about the basics of Lyme Disease and also discussed the use of single dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme Disease in patients with a tick bite. The sources we used are available here:

What is Lyme Disease?

Flagellated Spirochetes

Lyme is a name we give to a clinical syndrome caused by infection by the fastidious spirochete bacteria Borrelia Burgdorferi. Although the classic and most common presenting complaint is rash, Lyme can present with several different clinical manifestations. With few exceptions, it is a clinical diagnosis made by history and exam. Most cases can be managed as an outpatient although cardiac and neurologic complications occasionally need admission.

Where does Lyme come from?

B. Burgdorferi is transmitted by the ticks of the Ixodes species. In the Northeast, Ixodes Scapularis is the culprit, and in the Northwest, it is more commonly Ixodes Pacificus. Fortunately, they look nearly the same. Worldwide,there are several other species responsible.

The Mighty Tick!

Ixodes ticks are commonly referred to as “Deer Ticks”. This is because the White Tailed Deer is host for the tick, and tick populations are closely related to deer populations. The animal reservoir for B. Burgdorferi is rodents and birds (mice, chipmunks etc), NOT deer.

Notice Ixodes tick on the nose. Rodents are a primary animal reservoir for B. Burgdorferi

Ixodes ticks are born in the spring in the larval stage and are not infected at birth. They must progress through larval, nymph and adult stages prior to laying eggs. In each stage they need a blood meal. Most transmission to humans occurs from bites during the nymph and adult stages, meaning that the tick had fed on an infected animal during the at an earlier stage. Peak transmission occurs in May through July, when ticks are in the nymph stage, although transmission also occurs from adult ticks in the fall. Click Here to see a diagram.

Ixodes ticks do not fly and can only jump short distances. In the wild they are usually found on grass and plants. They must come in contact with a person, and this usually happens when a person walks through a grassy field.

I like to watch this one before I go to sleep each night.

Once on the skin, the tick burrows under the skin with its elongated mouth and starts to suck up the victim’s blood. The process of burrowing and taking the blood meal to engorgement takes at least 72 hours from time of contact. The actual Borrelia Burgdorferi bacteria lives in the gut of the tick, as well as the salivary glands, and is not immediately transmitted. In fact, transmission does not occur until at least 24 – 36 hours after the initial bite.

Dots represent confirmed cases of Lyme

Lyme Disease occurs throughout the United States. It is considered endemic to the Northeast, with hyperendemic areas in Westchester County, most of Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. There are also areas with considerable burden of disease in Minnesota and Wisconsin. The overall incidence is rising, likely as a result of warmer temperatures and more ticks surviving the winter.

Clinical Manifestations

It is useful to think of Lyme Disease occurring in three distinct syndromes:

- Early Localized

- Early Disseminated

- Late

Early localized

Early Localized Lyme Disease, the most common type of Lyme. The symptoms of early localized disease are Erythema Migrans (EM) as well as a constellation of other constitutional symptoms. Diagnosis is clinical and boils down to the presence of a single EM lesion in a patient with known or suspected tick exposure.

More than 80% of patients diagnosed with this type of Lyme disease have EM. While other symptoms can occur, including fatigue, myalgias, arthralgias and headache, none are specific, and only fatigue (54%) occurs in more than 50% of cases. (Nadelman 1996)

Laboratory tests available for B. Burgdorferi infection are both non-specific and insensitive at this stage.

Late engorged tick with EM rash beginning around bite

Central Erythema is common

Erythema Migrans (EM), the hall mark of Lymes, is an erythematous rash that extends outward from the site of a tick bite. It usually occurs within a few days to a few weeks after a bite. The rash is often macular, but may be slightly raised, is warm and occasionally pruritic.

Scabbing and skin necrosis is also common at center

EM is classically described as having a central clearing, however, this occurs in less than 30% of cases and the lack of central clearing should not rule out EM. More often, there can be a hyper-erythyma, scabbing or even necrotic skin at the center of the EM lesion. EM corresponds to actual spirochete infection of the dermis, and while not widely available or required for diagnosis, skin biopsies of the lesion can demonstrate the presence of B. Burgdorferi.

Early Disseminated Disease

While most cases of Lyme are isolated to the area surrounding the tick bite, about 20% of patients will show evidence of hematogenous spread of B. Burgdorferi. This is most commonly manifested by the presence of multiple EM lesions.

Multiple EM lesions in Early Disseminated Lyme Disease – From NEJM 2014 Clinical Practice

This finding does not correspond to multiple tick bites, but rather to the spread of the spirochete through the blood to other sites. Multiple EM lesions without other complications are treated the same as early localized disease, as an outpatient with oral therapy.

If a patient presents with Neurologic or Cardiac findings and EM, this is also considered Early Disseminated Disease.

Neurologic Lyme

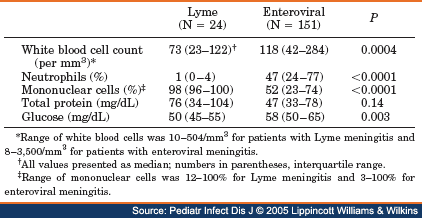

Lyme Disease can cause several neurologic symptoms. The most common is a cranial nerve palsy, frequently involving the facial nerve (CN VII). It can also present as meningitis (headache, nuchal rigidity) or radiculopathy. CSF findings are consistent with Aseptic Meningitis (slightly elevated WBC, pleocytosis and elevated protein, normal or near normal glucose, negative culture).

CSF Findings in Lyme vs. Viral Meningitis

Patients with suspected Lyme meningitis should be admitted, as the treatment is often intravenous (see below), and because it is clinically indistinguishable from early bacterial meningitis in the Emergency Department, and the results of CSF cultures should be obtained before discontinuing broad spectrum antibiotics. Isolated cranial nerve palsy or radiculopathy can be treated as an outpatient.

Cardiac Lyme

Just a little spirochete. Hanging out. IN YOUR HEART.

Infection involving the heart usually presents as varying degrees of atrioventricular block, which can be severe, including complete heart block. Notice the patient below with an EM lesion and complete (third degree) heart block.

EM Rash and Complete Heart Block

Current IDSA Guidelines recommend admission and parenteral therapy for second and third degree heart block, any heart block that is symptomatic (chest pain, dyspnea, syncope), and first degree block with significantly prolonged PR*, as this can worsen significantly before it improves.

Patients can also present with symptoms consistent with myopericarditis, however this is usually mild and does not progress to frank heart failure.

*IDSA guidelines say > 30 ms, which doesn’t make sense (normal < 200 ms), so…..you’re on your own!

Late Lyme Disease

Late Lyme Disease occurs months to years after tick exposure, and most cases have a history of untreated EM lesions. Late disease can manifest as arthritis or with neurologic symptoms. It is now rare to diagnose late Lyme Disease because most early cases are treated. However before we knew what caused Lyme, and how to treat it, a prospective group of patients with EM were followed, and 60% developed significant arthritis over the next few years.

Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common joint manifestation

Lyme Arthritis

Lyme Arthritis is mono or oligo articular, involving large joints, almost always the knee. Joint aspiration will be sterile, as B. Burgdorferi cannot be easily cultured. Synovial analysis will usually have intermediate WBC counts (25k – 100k) with PMNs and elevated eosinophils. (Kay 1988 Arthritis Rheumatology)

Late Neurologic Lyme

No you didn’t

Late Lyme Disease involving the nervous system can present as a chronic encephalopathy or encephalomyelitis. Untreated, it is slowly progressive. Late Neurologic lyme is very rare, with only a handful of cases each year. In a patient with a history of untreated lyme or possible lyme exposure and otherwise unexplained progressive neurologic findings, late neurologic lyme should be considered.

That’s it for this week! In an attempt to actually get people to read my post, I’ve split up into two parts. Stay tuned for next week’s installment of Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease – Part 2!

dzeccola

Latest posts by dzeccola (see all)

- Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease – Part 2 - October 11, 2016

- Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease – Part 1 - October 4, 2016

0 Comments