And now for the much anticipated conclusion of last week’s thriller (Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease Part 1). Last week we talked about what exactly is Lyme disease and how it can present a lot of different ways. This week we are going to talk about laboratory testing, co-infections, tick removal as well as treatment and prophylaxis for those with a tick bite.

Laboratory Testing

While culture media and PCR analysis for B. burgdorferi do exist, they are not widely available. At most hospitals three tests will be available, ELISA immunofloresence assay (IFA), as well as Western Blot for IgG and IgM to B. burgdorferi.

IFA is neither sensitive nor specific in early localized disease. While the specificity remains poor (high false positive), sensitivity improves in disseminated disease. When meningitis, arthritis or carditis are present, sensitivity approaches 100%, making this assay useful to rule out Lyme as a cause in an undifferentiated patient with these symptoms. Specificity is poor because the IgM assay will cross react with many other tick-borne diseases with a positive result.

If ELISA is positive a two-tiered approach is used and a second sample is sent for evaluation of IgM and IgG. (CDC Guidelines)

If a patient has EM, or EM and another symptom of lyme, laboratory testing is unlikely to improve diagnostic accuracy. Instead, patients should be treated empirically. (IDSA guidelines)

Laboratory testing becomes useful in a patient with symptoms that could be explained by Lyme disease but have no clear history of a tick bite or EM.

When to Suspect Co – Infection

Lyme can be co-transmited with several other zoonotic diseases. The most common are Babesiosis and Anaplasmosis. The infection rate of Babesia micorti in some tick populations is as high as 30%. Any patient who presents with suspected Lyme Disease who has significant hematologic derangement, a high fever, or appears toxic, should be evaluated and treated for these common co-infections.

What to do about a tick

If a tick is identified, it should be removed. Timing is key, as the disease is not transmitted until 24-36 hours after a bite. After about 24 hours the tick will start to be engorged, which can be used as a rough estimate if the exact time cannot be established.

People have come up with some pretty creative ideas for how to get rid of ticks, including salt, vaseline, and even lighting the tick’s body on fire.

Unfortunately, these techniques don’t work to reduce disease transmission. The correct approach is to use a pair of pointed tweezers, gently grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible, and apply gentle, persistent traction upward until the tick pops out. Just like in the creepy GIF below.

How about prophylaxis after a tick bite?

Giving patients a dose of meds is reasonable if some very specific conditions are met. Here is a quote direct from the IDSA guideline:

A single dose of doxycycline may be offered to adult patients (200 mg dose) and to children ⩾8 years of age (4 mg/kg up to a maximum dose of 200 mg) (B-I) when all of the following circumstances exist: (a) the attached tick can be reliably identified as an adult or nymphal I. scapularis tick that is estimated to have been attached for ⩾36 h on the basis of the degree of engorgement of the tick with blood or of certainty about the time of exposure to the tick; (b) prophylaxis can be started within 72 h of the time that the tick was removed; (c) ecologic information indicates that the local rate of infection of these ticks with B. burgdorferi is ⩾20%; and (d) doxycycline treatment is not contraindicated.

There is no data to support the use of other antimicrobial agents for routine prophylaxis after a tick bite.

Treatment of Diagnosed Lyme Disease

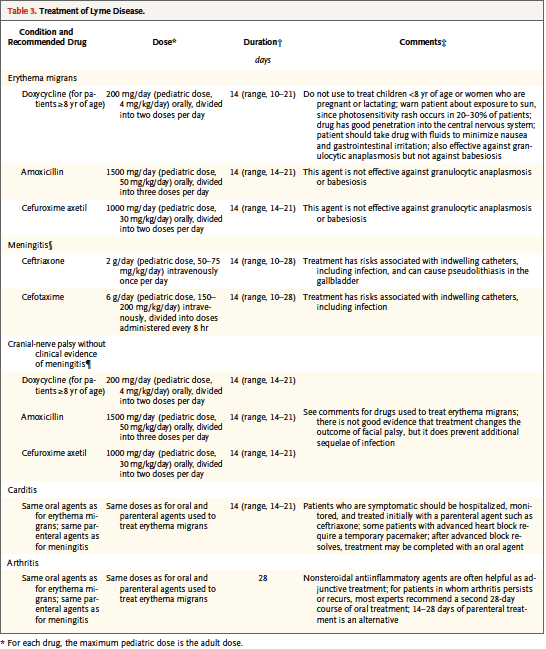

Treatment depends a great deal on the extent of disease and patient characteristics. The mainstays of treatment are doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxamine. Doxycycline is usually the drug of choice, because it is easily available, well tolerated, efficacious and also effective against Babesia micorti. However, it is important to remember that doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy and children < 8 years old. Generally, oral therapy is as effective as and safer than IV therapy, except when CNS penetration is needed, in which case ceftriaxone or a beta lactam is required. The following table from the NEJM Clinical Practice article summarizes it nicely.

Just like everybody’s other favorite spirochete (Treponema pallidum), treating Lyme can sometime cause a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, and patients should be warned to expect about 24 hours of feeling crappy after starting their medications.

TL:DR

- Lyme disease is transmitted by Ixodes tick after it has been attached for > 24 hours

- Disease can be prevented by preventing bites and removing ticks early

- In some specific cases, a single dose of doxycycline can precent disease in those with identified tick bites

- Early Local Lyme = Single Erythema Migrans

- Early Disseminated Lyme = Multiple Erythema Migrans and/or Meningitis, Carditis, CN Palsy

- Late Disease = Encephalitis, Arthritis

- Currently availble lab studies have poor test characteristics and are useful only for patients with equivocal history and symptoms

- Most patients are treated orally as an outpatient; those with cardiac and CNS infections are admitted for inpatient care

- Doxycycline is drug of choice (also kills Babesia), followed by amoxicillin and cefuroximine

- Beware of co-infections with Anaplasmosis, Erlichiosis and Babesiosis in sick-appearing people

dzeccola

Latest posts by dzeccola (see all)

- Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease – Part 2 - October 11, 2016

- Zeccola’s Zoo-o-Gnosis: Lyme Disease – Part 1 - October 4, 2016

0 Comments